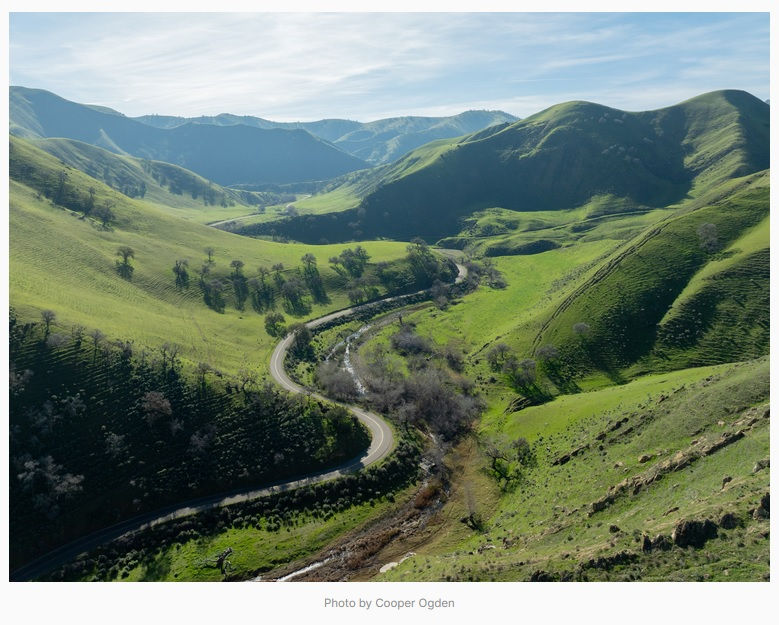

A closer look at some of the Native American archaeological sites and other historical features at risk of destruction from Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir

- savedelpuertocanyo

- Dec 6, 2025

- 8 min read

In Section 3.6-5 of the draft Environmental Report (dEIR) for Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir, they use the following to describe P-50-0344, a site they identify as a potentially “unique” archaeological site that might be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places and California Register of Historical Resources:

“Site P-50-344 is a prehistoric occupation site consisting of four bedrock mortars and cupule features, an artifact surface scatter of lithic debitage (stone chips and flakes from making stone tools), groundstone (a stone tool for grinding) fragments, and one obsidian biface tool fragment located along the slope and base of a hill overlooking Del Puerto Creek to the south. Subsurface testing at the site identified a deposit of lithic debitage, a bone awl fragment, burned faunal material, freshwater mussel shell fragments and marine shell beads. The features and artifact deposit at the site are indicative of habitation along Del Puerto Creek, containing information important in prehistory, specifically to the prehistoric inhabitants of the local area.”

This is just one of several sites that would be permanently destroyed if Del Puerto Water District is able to purchase these lands and build Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir. These sites should instead be preserved for inclusion in the pre-planned city park the reservoir would displace, along with other conservation areas for future generations to see first hand and learn from.

The fact that the current Tule River Yokuts and the Tachi Yokuts tribes represent a fraction of the peoples who used to inhabit the Central Valley and surrounding foothills is not well known. Before European contact, the Yokuts were a complex network of over 60 tribes. For a rough idea of what that means in terms of people, some estimates point to the area around Tulare Lake in the Central Valley supporting as many as 70,000. However, many California tribes fell victim to the successive blows of subjugation; the creation of the mission system by the Spanish, the continuance of those practices under the Mexican Republic, and then the forced relocation and genocide by Americans that accelerated around the time gold was discovered in California in the mid 1800s. Grinding rocks, milling stones, and other artifacts, along with their current placements along the creek and among the stands of blue oaks whose acorns were processed at these sites, serve as visceral reminders of the rich Hoyumne and Miyumne Yokuts and other communities that existed in places like Del Puerto Canyon before colonization. These sites are also important for those trying to learn more about and reconnect with their Indigenous roots.

The completely publicly-owned lands of multiple park systems offer protections for such sites and make allowances for ongoing Native American ceremonial or cultural practices associated with them. Lawmakers who have drafted legal protections for archaeological resources on public lands stressed their irreplaceability and importance to shared cultural history. Artifact sites on disputed properties, especially those that even prospective developers acknowledge as potentially “unique,” are just as valuable and should have more legal protections. This should include both legal requirements to stop certain developments that would destroy such locations and encourage both public and private property owners to provide access to tribal and Native American groups for educational and cultural purposes.

The fact that these sites are irreplaceable can’t be stressed enough. The idea that some of them need to be destroyed to make way for the relatively small Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir as a “compromise” for agribusiness interests is an inherently inequitable argument, especially since other alternatives that would let the water district meet some of its goals are available. Those public officials who are currently trying to pass legislation to fund Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir and remove some regulatory barriers for projects like it need to ask themselves: is a project that will knowingly destroy such irreplaceable pieces of both Native American and California history something that they want to continue to actively support? And for those officials who have been trying to make amends with California Native American Peoples for some of the historical wrongs perpetrated against them but also voiced support for Del Puerto Canyon Reservoir in the past, will they speak out against or take measures to stop it since these builders are planning to destroy sites that even they acknowledge are potentially significant and unique?

The push to conserve the Diablo Range, known to contain a rich diversity of both paleontological and archaeological sites, is a one-in-a-lifetime opportunity to save such areas for future generations. It also represents a relatively rare opportunity to better include input from Native American groups and to prioritize the protection of Native American history on a large scale. These irreplaceable sites are part of what makes this region special, and those lawmakers pushing for Diablo Range conservation should act soon to protect those areas currently under imminent threat of being destroyed. Prioritizing such areas for conservation with arrangements allowing members of Native American tribal and advocacy groups to access them is an important step for ensuring that any new park or conservation easement systems create inclusive spaces for historically underrepresented voices.

Del Puerto Water District has recently released a revised partial dEIR with assistance from Woodard & Curran’s Walnut Creek branch. This was paired with a public announcement by Del Puerto Water District expressing their desire to not hear comments on topics, like impacts to artifact sites, which they consider to be “sufficiently covered” in their first EIR. These turn of events have made the need for legislators and legal teams to step in and provide emergency protection for these sites more important than ever.

Una mirada más cercana a algunos de los sitios arqueológicos nativos americanos y otras características históricas en riesgo de destrucción del embalse Del Puerto Canyon

En la Sección 3.6-5 del borrador del Informe Ambiental (dEIR) para el Embalse Del Puerto Canyon, utilizan lo siguiente para describir P-50-0344, un sitio que identifican como un sitio arqueológico potencialmente “único” que podría ser elegible para su inclusión en el Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos y el Registro de Recursos Históricos de California:

“El Sitio P-50-344 es un sitio de ocupación prehistórica que consta de cuatro morteros de lecho rocoso y elementos de cúpula, una dispersión superficial de artefactos de desecho lítico (lascas y lascas de piedra provenientes de la fabricación de herramientas de piedra), fragmentos de piedra de cantera (una herramienta de piedra para moler) y un fragmento de herramienta bifacial de obsidiana, ubicado a lo largo de la ladera y la base de una colina con vistas al arroyo Del Puerto, al sur. Las pruebas del subsuelo en el sitio identificaron un depósito de desecho lítico, un fragmento de punzón de hueso, material de fauna quemada, fragmentos de concha de mejillón de agua dulce y cuentas de concha marina. Los elementos y el depósito de artefactos en el sitio indican que hubo habitación a lo largo del arroyo Del Puerto y contienen información importante para la prehistoria, específicamente para los habitantes prehistóricos de la zona.”

Este es solo uno de los varios sitios que quedarían destruidos permanentemente si el Distrito de Aguas de Del Puerto pudiera adquirir estos terrenos y construir el Embalse del Cañón del Puerto. En cambio, estos sitios deberían preservarse para incluirlos en el parque municipal preplanificado que el embalse desplazaría, junto con otras áreas de conservación para que las generaciones futuras las conozcan de primera mano y aprendan de ellas.

No se conoce bien que las actuales tribus Yokuts del Río Tule y Tachi Yokuts representen una fracción de los pueblos que habitaban el Valle Central y las colinas circundantes. Antes del contacto europeo, los yokuts constituían una compleja red de más de 60 tribus. Para tener una idea aproximada de lo que esto significa en términos de población, algunas estimaciones indican que el área alrededor del lago Tulare, en el Valle Central, albergaba hasta 70 000 personas. Sin embargo, muchas tribus de California fueron víctimas de los sucesivos impactos de la subyugación: la creación del sistema de misiones por los españoles, la continuación de estas prácticas bajo la República Mexicana y, posteriormente, la reubicación forzosa y el genocidio perpetrado por los estadounidenses, que se aceleraron en torno a la época en que se descubrió oro en California a mediados del siglo XIX. Piedras de moler, piedras de molino y otros artefactos, junto con su ubicación actual a lo largo del arroyo y entre los robles azules cuyas bellotas se procesaban en estos sitios, sirven como recordatorios viscerales de los ricos Hoyumne y Miyumne Yokuts, así como de otras comunidades que existían en lugares como el Cañón del Puerto antes de la colonización. Estos sitios también son importantes para quienes buscan aprender más sobre sus raíces indígenas y reconectarse con ellas.

Los terrenos completamente públicos de múltiples sistemas de parques ofrecen protección para dichos sitios y permiten las prácticas ceremoniales o culturales de los nativos americanos asociadas a ellos. Los legisladores que han redactado leyes de protección para los recursos arqueológicos en terrenos públicos destacaron su irremplazabilidad e importancia para la historia cultural compartida. Los yacimientos arqueológicos en propiedades en disputa, especialmente aquellos que incluso los posibles promotores inmobiliarios reconocen como potencialmente "únicos", son igualmente valiosos y deberían contar con mayores protecciones legales. Esto debería incluir requisitos legales para detener ciertos desarrollos que destruirían dichos lugares y alentar a los propietarios de propiedades públicas y privadas a brindar acceso a grupos tribales y nativos americanos con fines educativos y culturales.

No se puede enfatizar lo suficiente el hecho de que estos sitios son irremplazables. La idea de que algunos de ellos deban ser destruidos para dar paso al relativamente pequeño embalse Del Puerto Canyon como un "compromiso" para los intereses de la agroindustria es un argumento intrínsecamente injusto, especialmente considerando que existen otras alternativas que permitirían al distrito de agua cumplir algunos de sus objetivos. Los funcionarios públicos que actualmente intentan aprobar leyes para financiar el embalse Del Puerto Canyon y eliminar algunas barreras regulatorias para proyectos como este deben preguntarse: ¿es un proyecto que destruirá a sabiendas piezas tan irremplazables de la historia de los nativos americanos y de California algo que desean seguir apoyando activamente? Y aquellos funcionarios que han intentado resarcir a los Pueblos Nativos Americanos de California por algunos de los agravios históricos perpetrados contra ellos, pero que también expresaron su apoyo al embalse Del Puerto Canyon en el pasado, ¿se pronunciarán en contra o tomarán medidas para detenerlo, ya que estos constructores planean destruir sitios que incluso ellos reconocen como potencialmente significativos y únicos?

El esfuerzo por conservar la Cordillera Diablo, conocida por su rica diversidad de yacimientos paleontológicos y arqueológicos, representa una oportunidad única para preservar estas áreas para las generaciones futuras. También representa una oportunidad excepcional para integrar mejor las aportaciones de los grupos Indígenas estadounidenses y priorizar la protección de su historia a gran escala. Estos sitios irremplazables son parte de lo que hace especial a esta región, y los legisladores que impulsan la conservación de la Cordillera Diablo deberían actuar con prontitud para proteger estas áreas que se encuentran actualmente en peligro inminente de destrucción. Priorizar la conservación de estas áreas y establecer mecanismos que permitan el acceso de miembros de tribus Indígenas estadounidenses y grupos de defensa es un paso importante para garantizar que cualquier nuevo sistema de parques o servidumbres de conservación cree espacios inclusivos para las voces históricamente subrepresentadas.

El Distrito de Aguas de Del Puerto publicó recientemente un Informe de Impacto Ambiental (EIR) parcial revisado con la asistencia de la sucursal de Walnut Creek de Woodard & Curran. Esto se complementó con un anuncio público del Distrito de Aguas de Del Puerto en el que expresó su deseo de no escuchar comentarios sobre temas como el impacto en los sitios arqueológicos, que consideran suficientemente cubiertos en su primer EIR. Estos acontecimientos han hecho que la necesidad de que legisladores y equipos legales intervengan y brinden protección de emergencia a estos sitios sea más importante que nunca.

Comments